At the International Islamic University of Malaysia (IIUM), in the country’s capital Kuala Lumpur, Russian student Jeyhun Jaafar posts a video on a social network.

At the International Islamic University of Malaysia (IIUM), in the country’s capital Kuala Lumpur, Russian student Jeyhun Jaafar posts a video on a social network.

A comment pops up in Turkish – a language Mr Jaafar does not speak. But he is able to respond with the help of a translate button on the page.

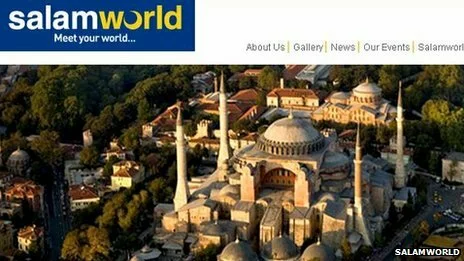

This is one of the ways the new social network, called Salamworld, hopes to make it easier to connect Muslims around the world.

In Malaysia, Muslims make up 60% of the 29 million internet users.

Besides this South East Asian country, a trial version of Salamworld is currently being tested by about 1,000 users in Bosnia-Hercegovina, Turkey, Egypt and Indonesia.

The company aims to launch globally by November.

At first glance, Salamworld may not seem much different from other social networks.

With a blue and white layout and features such as a wall to post comments, photos and videos, it is similar to what networking giant Facebook used to look like when it first launched.

But supporters of the multilingual and multicultural project say one thing will be different – content.

Salamworld aims to create a safe space for Muslims – free from things such as pornography, gambling and anything else that may be against Islamic principles.

For instance, Prof Nuraihan Mat Daud of IIUM, who uses Western social networking sites as a teaching tool, says she is uncomfortable with advertisements that show women in revealing clothing.

Although Facebook is tough on pornography, it sports a number of gambling apps – including one called Bingo Friendzy that allows UK users aged 18 and over to play games for real-money prizes.

Local rules

It is not the first attempt to create a Muslim-tailored social network, but so far none has become popular on a large scale.

Finland-based Muxlim.com came out in 2006, but is currently shut down. Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood launched Ikhwanbook.com in 2010 but the site is also currently offline.

Critics say that these networks tended to appeal only to their respective regions.

Salamworld, based in Turkey but with advisers from more than a dozen countries, hopes to be different.

One way it aims to achieve the goal of uniting Muslims globally is by using a three-level content-filtering feature.

It will allow authorities to set content guidelines based on different interpretations of Islam, which vary from country to country. For example, a picture of a Muslim woman who is not wearing a hijab may be fine in secular Indonesia but not acceptable in Saudi Arabia.

It is not clear how internet users will react to such censorship – in Malaysia, for instance, attempts to control the web have been met with fierce opposition.

Earlier this month, politicians and activists staged an internet blackout day to protest against changes in the law they say aimed to stifle free speech online.

Some Malaysians, however, say they will tolerate a certain degree of censorship, such as filtering out photos of skimpy outfits or alcohol ads, which are against Islamic values.

“But if they are censoring things for political reasons, like to prevent us from seeing the real situation in Syria or the violence committed against Muslims in Burma, then that is not OK,” says another student, Abdul Hadi bin Haji.

‘Alternative needed’

Even if Muslims around the world do start using Salamworld en masse, it may still be tricky to rival Facebook, say analysts.

According to internet information company Alexa, the social networking giant is the most popular site in all the countries where Salamworld is conducting its trials.

In Malaysia, for example, many say it is at times easier to connect with friends through Facebook than by calling them.

It doesn’t worry Salamworld’s head of Asia-Pacific operations Salam Suleymanov, who strongly believes in a need for an alternative.

“When we talk about 1.5 billion Muslims, maybe those who support my view make up a very small percentage – but it’s still a big number,” he says.

SOURCE:NEWS TESHNOLOGY